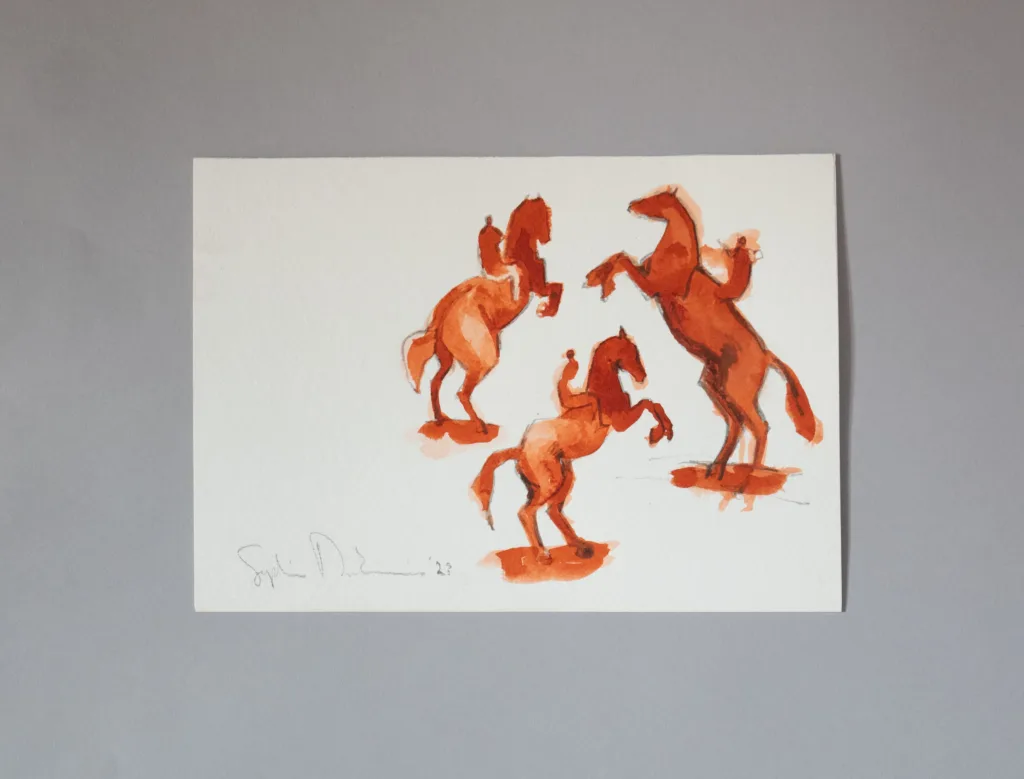

For me the Apocalypse concerns the time of a final reckoning. During lockdown, I wanted to express my feelings about the causes of covid, and the way that right wing politics was taking over the world. Revelations is rich in imagery, used by many artists in the last few hundred years to convey to the illiterate masses the horror of the end of the world that awaits. As a student of the history of art at the Courtauld Institute in London, I became well versed in the kind of imagery used, and in this case particularly the etchings of Albrecht Durer. I painted a mural of the horsemen galloping up the stairs (3 with animal heads, and one with an empty cage), to reflect the cruel animal practices in Chinese wet markets, and the anger that I felt. On the landing, I painted the whore of Babylon riding the seven headed beast. Each head of the beast was a portrait of a right wing politician, including Trump, Netanyahoo, Johnson, Putin and Bolsonaro. She held in her hands the cup of filth, the poisons and evil of the world. So when the chance came to make an exhibition for Crumb Gallery, I wanted it to reflect the fear and impotence I felt in regard to Ukraine, Gaza, disappearing democracies and the spectre of Totalitarianism. The horsemen of the Apocalypse in this respect no longer represent vengeful beasts. They represent the rush towards our loss of freedom – human riders responsible for the chaos that will accompany that loss. Red for war, black for famine, white for conquest and palor for death. The ink running out of control, the stains that grow on

the paper which can never be washed away.

Revelations

Horseman of the Apocalypse

Review Outake

“…Reflects the current climate we are experiencing, dark and dramatic situations linked to wars and conflicts, which loom in this precise historical moment. The term Apocalypse is commonly referred to the Apocalypse of St. John the Apostle or Book of Revelation, in the New Testament, written during his exile on the island of Patmos, and is generally interpreted as the prophecy of the “end of the world” or rather as “ revelation of the events of the end times”. The figures, symbols, mysterious and fantastic elements of this visionary narrative have aroused great fascination over the centuries, inspiring much literature and many representations of sacred art, starting from the art of the Carolingian era. Artists such as Cimabue, Giotto, Signorelli, the Van Eyck brothers, Dürer, Rubens, El Greco, among others, have grappled with these themes. Sophie Dickens, following this line, has studied and studied in depth the series of fifteen woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (1496-1498) and in this exhibition she focuses on the four seals, told in the sixth book, which when opened give life to the four knights of Apocalypse, on as many horses, one white, one red, one black and one greenish to symbolize: war, death, famine and pestilence. In the center of the space, the artist placed the great knight with his fiery red horse, brandishing his sword. The horse has its legs raised, you think you hear it neigh and gallop away. War. Great apocalyptic knight is a two-metre sculpture, made with recycled larch, chestnut and pine boards from the renovation of the Albergo dell’Angelo in Pieve di Teco, where the sculptress lives in Liguria, combined with resinous glue, ink and pigment sienna red.

Sophie’s sculptures all have a distinctive trait. He builds armor with metal bars, as if they were skeletons, on which he then applies pieces of specially processed material. Her subjects reflect a modern primitivism, they are fantastic images that refer to nature, mythology, classical iconography, which she arrived at thanks to the History of Art, through the observation of artists such as Michelangelo or Titian. She creates movements made of bones, muscles and tendons that recall the studies of the photographer Eadweard Muybridge which, as she says, influenced her along her path. That Muybridge who invented the zoopraxiscope, to study and reproduce the movement of animals, famous for the sequence of photographs called The Horse in motion. Next to the Red Knight, on display, there are other small sculptures, which depict all four knights, together and ink drawings on paper, preparatory studies as well as in the practice of the great Renaissance masters. They are works in which the echo of the horses of the great battles can be perceived, such as that of San Romano painted by Paolo Uccello.

In the text in the catalogue, edited by Rory Cappelli, published by Crumb Gallery for the occasion (NoLines series), the artist explains the choice of this theme: “I wanted my Apocalypse to reflect the fear and impotence I feel in against Ukraine, Gaza, dying democracies and the specter of totalitarianism. The horsemen of the Apocalypse in this respect no longer represent vengeful beasts. They represent the rush towards our loss of freedom, and they are responsible for the chaos that will accompany that loss.” As Rory Cappelli underlines “the reflection is on violence, on war, on conflicts, on the lack of hope. Yet, it is not this, the lack of hope, that those horses soaring in the sky give to those who observe them.” In Greek Apocalypse means “revelation” and as claimed by the scholar Paul Beauchamp, one of the most important biblical scholars, the deepest message of these texts is linked to change, there are times that require a change of direction, the end of a story and the beginning of another, “apocalyptic literature was born to help us endure the unbearable”. It was born to give hope, to tell that evil will, in the end, be defeated. And this is precisely the message that Sophie Dickens wants to leave us.

Apocalypse will remain open until May 25, 2024.”

Words by Rory Cappelli

“Art does not reproduce what is visible, but it makes visible what is not always visible,” Paul Klee told his students. He was talking about his art; he was thinking about the ability to create images by drawing on dreams, shadows, the unconscious; with his colors and objects he was evoking the mystery of the cosmos. Making visible that is, which is not always so, however far apart the two artists are in every possible sense, is a thought that comes to mind when faced with Sophie Dickens’ sculptures, that almost supernatural ability to render movement, with a simple piece of wood. Simple. It sounds simple, but there is nothing simple about the work of this British artist who has now chosen Italy, Liguria, as her home. Behind every line, every curve, every gesture, every figure, there are years of study, years of trial and error, of reflection and defeat, of sudden victories and more trial and error. One grasps all this when faced, for example, with the sculpture Judo that Dickens made for the 2012 London Olympics: a judo move rendered in what appears to be a round, fluid movement, with roughness reminiscent of Giacomo Balla. A simple movement, indeed. But one that is the perfect synthesis of the clash-meeting of two bodies, a sculpture that succeeds in conveying more than any lecture the essence of judo with its maximum use of energy (Seiryoku Zen’yo) and the personal progress that is achieved only with the

cooperation of others (Jita-Kyoei). Sophie Dickens, who majored in art history at the Courtauld Institute, attended the Sir John Cass School of Art and studied at the anatomy department of University College, also in London, has an explosive and irrepressible energy, an almost magical creativity, and a deep, extensive and never trivial culture. Her works are often echoes of stories, masters, mythology, as in the Minotaur, Hercules, Leda, and Fallen Angels, so much so that it is not surprising that on the wall of her studio is written, “Mythological subjects represent universal truths “

That knight with his fiery red horse and equally red sword, standing two meters tall astride his steed, standing with raised legs, looking as if he is about to gallop off and soar into the sky, is the sculpture “War. Great Apocalyptic Horseman.” Its materiality – reclaimed larch, chestnut, and pine boards from the renovation of the Albergo dell’Angelo in Pieve di Teco, combined with resin glue, ink, and red pigment from Siena – blends with the lightness that pervades it all, an oxymoron that is one of Dickens’ many artistic skills. As tragic as the theme is, there is indeed a kind of placid, candid hope to be found in her sculptures, emanating from the grain of the wood or in the marks on the metal in which the figures themselves are cast. Whether it is the wolves, an endangered species, hunted, hated, reiected, howling at the moon or searching for each other in the foliage of trees, or the wild boars, similarly killed, persecuted, pursued, or the owls spreading their wings in search of the sky, or mice, pelicans, ducks, hares, dogs, monkeys there is always a promise that erupts from the materiality leaving a sense of hope and struggle. Powerful.

Even in the theme of these sculptures, the Apocalypse-which Dickens studied and loved in her time at the Courtauld Institute in the series of fifteen woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (1496-1498)-the reflection is on violence, war, conflict, and hopelessness. Yet it is not this, the hopelessness, that those horses hovering in the sky give to those who watch them. But the urge to break free from chains, to run, inflating lungs, into freedom. Or the unawareness of the certain end toward which one ventures preciselv without awareness. “Revelation is a richly imagined tale, almost a collection of iconography used over the centuries by many artists to convey to the masses the horror of the end of the world,” Sophie Dickens explains. “I wanted my Apocalypse to reflect the fear and helplessness I feel about Ukraine, Gaza, dying democracies and the specter of totalitarianism. The horsemen of the Apocalypse in this respect no longer represent vengeful beasts. They represent the race toward our loss of freedom, and they are responsible for the chaos that will accompany that loss. Horses and horsemen are, in keeping with tradition, red for war, black for famine, white for conquest, and pale for death.” Alongside small and large sculptures on the theme, Dickens has also made small works where, she says, “the ink flows out of control, with stains growing on the paper that can never be removed.” The works on paper on Dickens’ Apocalypse also operate the same curse as the sculptures: the “indelible” spots seem to rush out of the frame, and keep going, as in Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs. To get out there, where we too will see them in all their horror and beauty, where “loss of freedom and chaos reigns,” where perhaps by being

able to alimose tragedv through these reflections on wood, metal and paper we will be able to find our wav back. Indeed, art sometimes “makes visible what is not alwavs visible.”